“No Inventions; No Innovations.”: What Happened to Flying Cars & Hoverboards?

Let’s talk about the 1st billion-dollar company in the world (the OG unicorn, you could say): U.S. Steel. It was just acquired by Japan’s Nippon Steel (once only <1% of its size).

How did this happen?

In 1901, U.S. Steel incorporated as the largest company in the world, producing over ⅔ of domestic steel. By 1945, U.S. Steel was literally producing 60% of the world’s steel.

But, as Fortune characterized in 1936, U.S. Steel’s strategy was “No inventions; no innovations.”

Time and time again, U.S. Steel resisted developing or even adopting new technologies, banking on its global dominance at the time (Europeans were far behind, and the Japanese were at <1% of U.S. Steel production).

Then came 1948: A Swiss engineer developed the Basic Oxygen Process (BOF), a cheaper and more efficient process that produced higher quality steel. This was quickly adopted by the Austrians & the Japanese. U.S. Steel once again lagged behind.

“No inventions; no innovations.”

By 1970, 50% of the world’s steel was being produced by BOF. By 1971, Japan’s Nippon Steel surpassed U.S. Steel in the global market.

Fast forward to 2001, a century after formation: U.S. Steel accounts for a mere 8% of domestic consumption (still 1st in the US… but among dozens of U.S. steelmakers suffering bankruptcy), leading to its eventual acquisition by Nippon Steel in 2023.

U.S. Steel’s story is a lesson to the consequences of investments without innovation or invention. And a warning to the dangers of complacency.

Now, let’s apply this to “tech” – an industry with many billion-dollar unicorns.

1950s kickstarted an era of inventions and discoveries. Soon, kids were watching The Jetsons (Assuming George was born in 2022, the age of floating cities should be on our horizon). Young professionals were sure they’d be riding hoverboards to work.

Inventions start with capital.

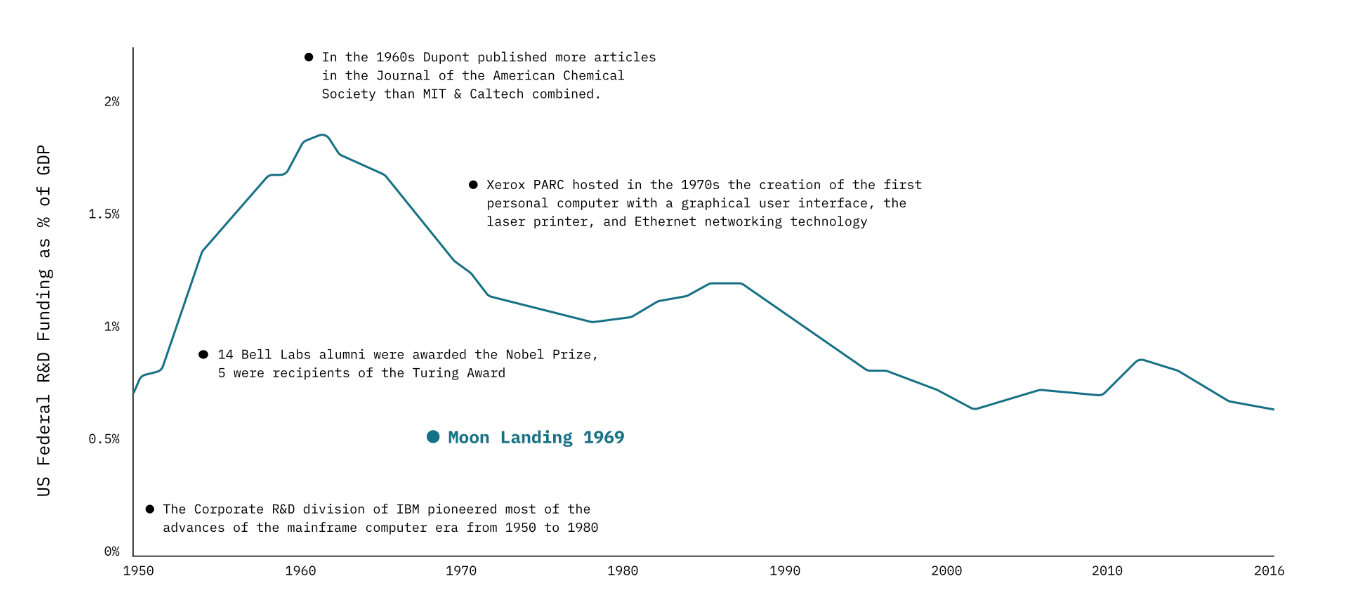

By the 1960s, US government investment in scientific discovery reached its height at close to 2% of GDP (worth over $1.3T in today’s currency). Simultaneously, as we all know, large private companies launched R&D divisions (e.g. Bell labs) that drove an era of scientific discovery that unlocked new frontiers.

IBM pioneered most of the advances in the mainframe computer era. Xerox PARC hosted the creation of the first personal computer with a graphical user interface, the Maser printer, and Ethernet networking technology. Bell Labs developed radio astronomy, the transistor, the laser, the photovoltaic cell, the Unix operating system, the programming languages (B, C, C++, etc.), winning Nobel Prizes and Turing Awards. Dupont published more in JACS than MIT and CalTech combined. We landed on the moon.

This was the era of science.

Then, in the 1980s, deep R&D pockets evaporated. Corporations cut their R&D divisions. Federal funding waned.

In its place rose venture capital – the new driver of “innovation” (i.e the adaptation and application of existing discoveries), investing widely from Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook to e-commerce apps, enterprise SaaS, fintech software platforms, etc. “New” breakthroughs weren’t necessary when there was still plenty to be built on the foundations of already developed science and technologies (and make a f-ton of money along the way).

Epitomized famously by Peter Thiel: “We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

So, here we are, rapidly approaching our own version of U.S. Steel’s 1948.

As we exhaust the iterative innovations powered by discoveries of the prior generation, there are fewer and fewer truly new innovative businesses to invest in. In fact, when you search today for a timeline of scientific and technological achievements since 1990, you might be impressed. It seems as if we’ve built so much. When you dig back through that list and consider what has been built on the scientific discoveries of the past, less so.

We need new breakthroughs to tackle our most pressing problems. What’s the next “semiconductor” material? How do we unlock faster computing and more data storage? What’s the magical new renewable energy source to help reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and to reduce global CO2 emissions? Or our growing population’s needs for natural resources like water? Or our aging population’s healthcare needs? Or the swiftly evolving bacterial and viral threats? These are just some of the impending problems that cannot be easily solved by yesterday’s science.

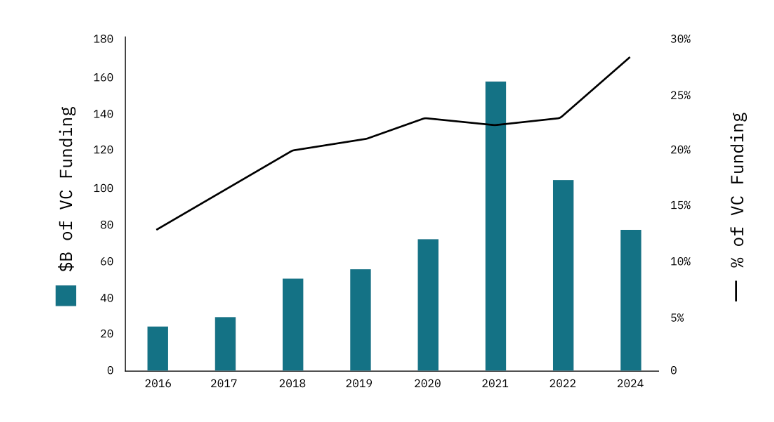

Maybe venture capital as a whole is starting to see the light. (Or maybe we just realized the sheer scale of these markets. I mean, whoever helps uncover the next “semiconductor” will unlock unimaginable market potential — and a f-ton of money).

Either way, data shows that venture capitalists are beginning to catch on. Venture funding of science-related technologies (once derided as mere “science projects”) has more than 2x’ed in the last decade – 12% in 2013 to 28% in 2023.

Alternative energy sources like hydrogen, battery technology, and quantum computing are among the front runners for funding. These and other pockets of private capital have managed to keep some fields of science alive. CRISPR and the Human Genome Project. MIT’s 5-atom quantum computer. NASA’s James Webb telescope. Electric cars and the new space race (Thanks, Elon). Literally in the last 24 hours, Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus became the 1st private spacecraft to land on the moon (and 1st US spacecraft since Apollo 17 over 50 years ago) — launched by SpaceX.

But let’s not forget the other unfortunate side effect of the rise of available venture capital for software startups: scientific brain drain. An increasing proportion of science and engineering talent have been leaving academia and research where the discoveries of the 20th century were born.

The data doesn’t lie: The number of science and engineering PhD recipients grew by 74% from 2002 to 2022. However, the proportion of PhDs taking jobs in business and industry in the United States has doubled from 24% to 48%. This is even more compounded in STEM fields, e.g. engineering (78.8%), physical sciences (75.3%), math and computer science (69.8%), and life sciences (54.1%). After all, PhDs can make significantly more building apps than spending their time in research.

So, who can blame them? We show what’s important with our dollars, right?

But now who’s left to be our frontline of scientific discovery?

We must do better. We need brilliant and curious minds to see that innovation and discovery are just as valued as trendy software startups and industry “disrupting” apps. That the outcomes of their work are just as valued. And have the potential to pay as fruitfully as building on top of existing technologies.

We need to put our money where our mouth is.

At the peak of R&D funding, we viewed sci-fi as around-the-corner possibilities.

In 2024, in a world running out of necessary raw materials with our most innovative minds building yet another social app, George Jetson is still in his infancy, and Rosie is a Roomba with a cat riding on it.

Flying cars will not be built on carbon steel frames fueled by the combustible fossil fuels of today.

But there’s hope for Rosie yet: Scientists and inventors now have access to the tools that will be able to accelerate discoveries, grow adoption, and scale at speeds we are just beginning to understand — at last, leveling the playing field in their competition for capital. (More on that next week!)

More Reading You May Find Interesting:

US Steel Acquisition: Reuters, “Japan's Nippon Steel to acquire U.S. Steel for $14.9 billion”

US Steel History: Construction Physics, “‘No inventions; no innovations,’ a History of US Steel”

Corporate innovation information: BCG "Deep Tech: The Great Wave of Innovation"

Federal R&D Funding: Council on Foreign Relations "Innovation and National Security: Keeping Our Edge"

PhD statistics: Forbes "Number of Doctoral Degrees Awarded in U.S. Rebounds to All-Time High"

BCG "An Investor's Guide to Deep Tech"

VC funding volume: Dealroom.co "Global tech & VC Q3 2023"

The Odysseus Moon landing: New York Times, “Highlights From the Successful Lunar Landing of the Spacecraft Odysseus”